losing patience with patients

--------------------

--------------------

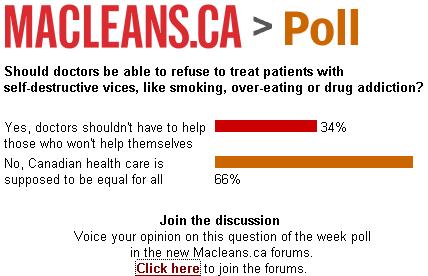

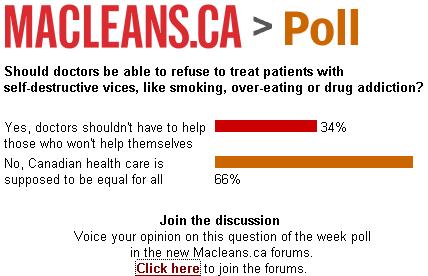

Health care is meant to be open to everyone equally. But some doctors question, even deny, treatment to those with certain vices. At issue: health care for patients with self-destructive vices -- overeating, smoking, drinking or drugs. More and more doctors are turning them away or knocking them down their waiting lists -- whether patients know that's the reason or not. Frightening stories abound. GPs who won't take smokers as patients. Surgeons who demand obese patients lose weight before they'll operate, or tell them to find another doctor. Transplant teams who turn drinkers down flat. Doctors say their decisions make sense: why spend thousands of dollars on futile procedures? Or the decision is the product of frustration: why not make patients accountable for their vices? Others call it simple discrimination. But in a health system with more patients than doctors can treat, where doctors have discretion over whom they'll take on, some say it's inevitable that problem patients will get shunted aside in favour of healthier, less labour-intensive cases. So here's the question: if people won't stop hurting themselves, can they really expect the same medical treatment as everyone else?

While I appreciate the logic behind some of the arguments, especially with respect to smoking, drinking, and the use of illicit drugs, it may be a different story for obesity. There is, of course, the research out there that suggests there may be genetic links that increase the likelihood of becoming obese. But the situation is different for plainer reasons of equity: poor eating habits and obesity have also been linked to lower-income households (some may say the same holds true for drug use, etc.). If the essential effect of this screening is that we end up refusing health care for the more disadvantaged members of society, then we need another solution to the resource and doctor-availability problem.

Of course, people need to be accountable for their choices and actions. The "right" to health care comes with the responsibility of co-operating with one's physician when s/he makes recommendations for one's well-being. Dr. Bill Pope, registrar of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Manitoba, argues that "by refusing to accept advice related to major issues with the patient's health, the patient is saying to the doctor, I don't believe you, I can't trust you, I can't accept you -- and is basically saying I can't work with you." It comes as no surprise then, that in a "culture of indifference and lack of accountability" -- the "me and my rights" mentality -- many doctors are simply losing patience with their patients.

Of course, people need to be accountable for their choices and actions. The "right" to health care comes with the responsibility of co-operating with one's physician when s/he makes recommendations for one's well-being. Dr. Bill Pope, registrar of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Manitoba, argues that "by refusing to accept advice related to major issues with the patient's health, the patient is saying to the doctor, I don't believe you, I can't trust you, I can't accept you -- and is basically saying I can't work with you." It comes as no surprise then, that in a "culture of indifference and lack of accountability" -- the "me and my rights" mentality -- many doctors are simply losing patience with their patients.

--------------------

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home